Picasso famously said, “It took me four years to draw like Raphael, but a lifetime to draw like a child.”

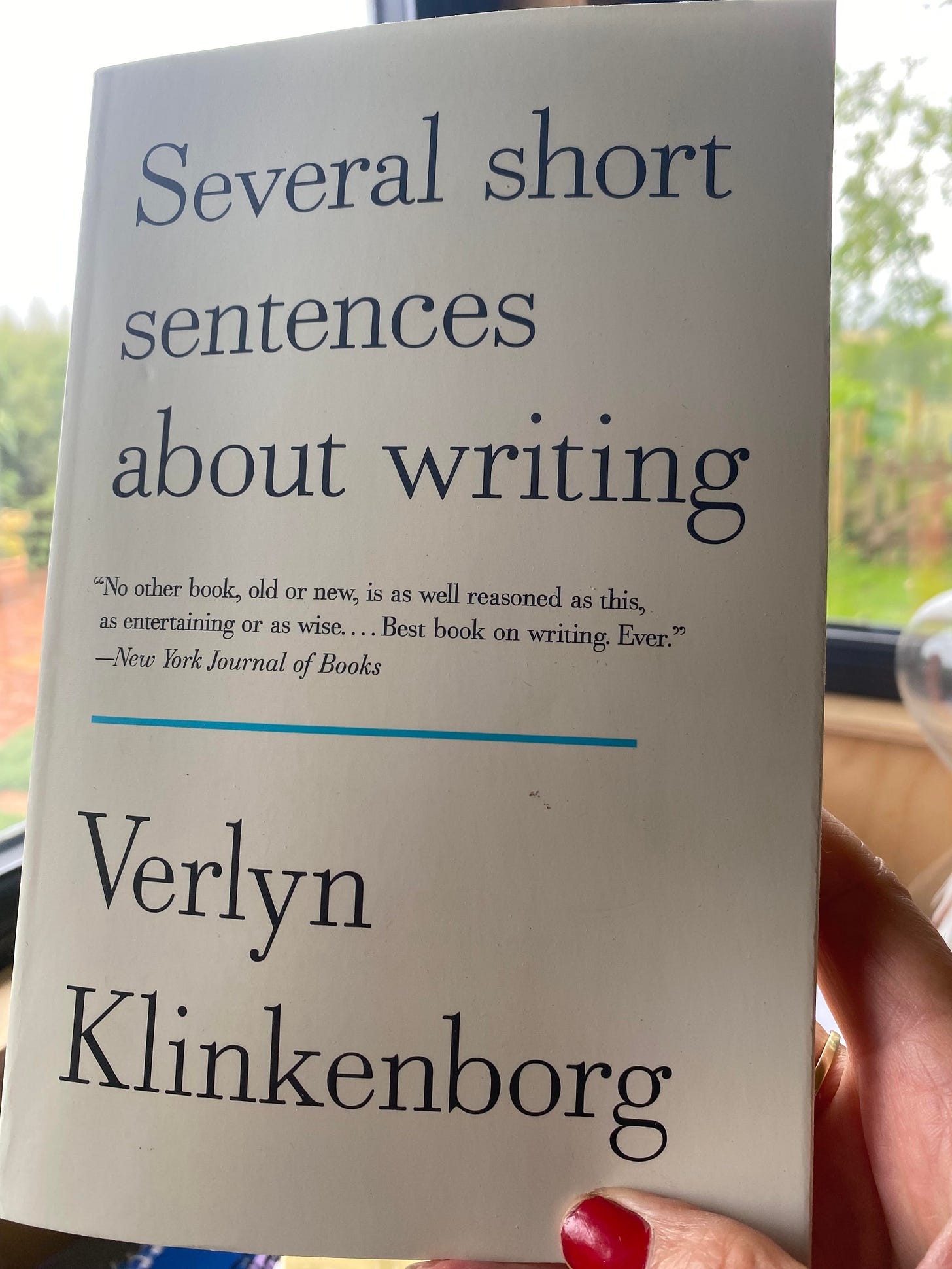

I am currently reading and enjoying Verlyn Klinkenborg’s “Several short sentences about writing’”.

In this delightful, playful but informative book I find the following question.

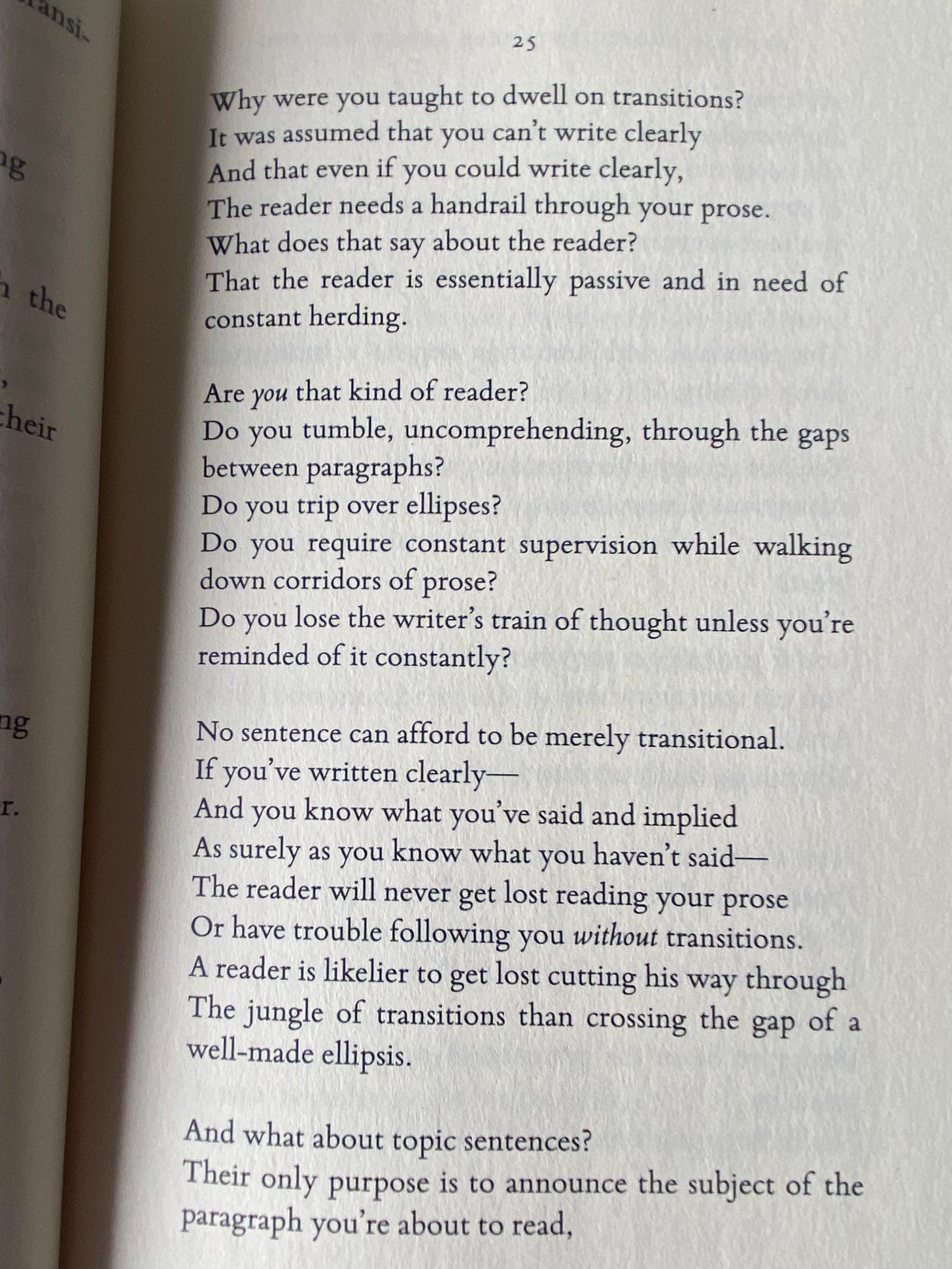

“What if you value every one of a sentence’s attributes and not merely its meaning?”

Klinkenborg goes on to suggest.

“Strangely enough, this is how you read when you were a child.

Children read repetitively and with incredible exactitude.

They demand the very sentence – word for word- and no other.

The meaning of the sentence is never a substitute for the sentence itself,

Not to a six-year-old.

This is still an excellent way to read.”

I’m familiar with Picasso’s quest to draw like a child and understand this. The immediacy, originality and certainty with which a young child portrays the world has truth and energy.

But I have never considered the idea of reading like a child.

Reading to a child

I have tried, when reading a bedtime story to a child, to paraphrase, or skip a page, as a means of shortening the experience. They won’t let me get away with it. As Klinkenborg points out, to the child every word is precious and necessary.

How did I read as a child? I remember the glamour of words, their addictive charms. How I loved to chant over and over, “Double double toil and trouble, fire burn and cauldron bubble” for the song of the words, for the seething, bubbling, bounce of them.

Weaving spells. Words were magic.

I still think they are.

But a lot of the time I forget this.

Reading as Thinking

Reading is so much more than thinking but it can descend into an intellectual activity.

Harvesting sentences for meaning and admiring the cleverness of making connections and solving puzzles. Reading through the words as if they were glass interested only in the ideas or images that they carry.

Reading as Play

But if I remember the way a child reads, or is read to, I think more about the sound and rhythm of the words. I think about the shape of the words and how they look on the page.

"Tyger, tyger burning bright

In the forest of the night

Reading Better

“You can only become a better writer by becoming a better reader.” Klinkenborg again.

I have been working on my reading.

Sounds and wonders

I’m a member of the Royal Literary Fund Reading Round Group in Norwich led by the poet Heidi Williamson. She has introduced us to new writers through their short stories and poems. Although I read poetry I mainly stick to poets I know and like. I’ve never been that keen on short stories. Alice Munroe is the only short story writer I read for pleasure and her stories are so dense they’re like novels.

But its been great to be exposed to so many new forms and voices.

Heidi brings one new short story and one new poem each week and reads these to us. I first receive this new writing as I did as a child - aurally. And because of this the works exist in a more three-dimensional way than if I’d just read them to myself in my head.

Reading aloud

It’s so nice being read to. I can see why audio books are popular. There’s something special about being read to live in a group where everyone receives the words at the same time.

Each hears the story in their own way, same story multiple responses.

I’m very quick to pick up meaning but others in the group help me appreciate the sounds and shapes, the atmospheres and allusions.

What is said in the silence around the words.

My reading is enhanced by the reading of others.

The layout

Reading poetry has made me more conscious of how words look on a page.

How the layout impacts the reading. I’m learning more about how punctuation and line breaks affect the rhythm of sentences.

The impact of writing is created through these sounds and pictures just as much as through the story and meaning that the sentences build up to create.

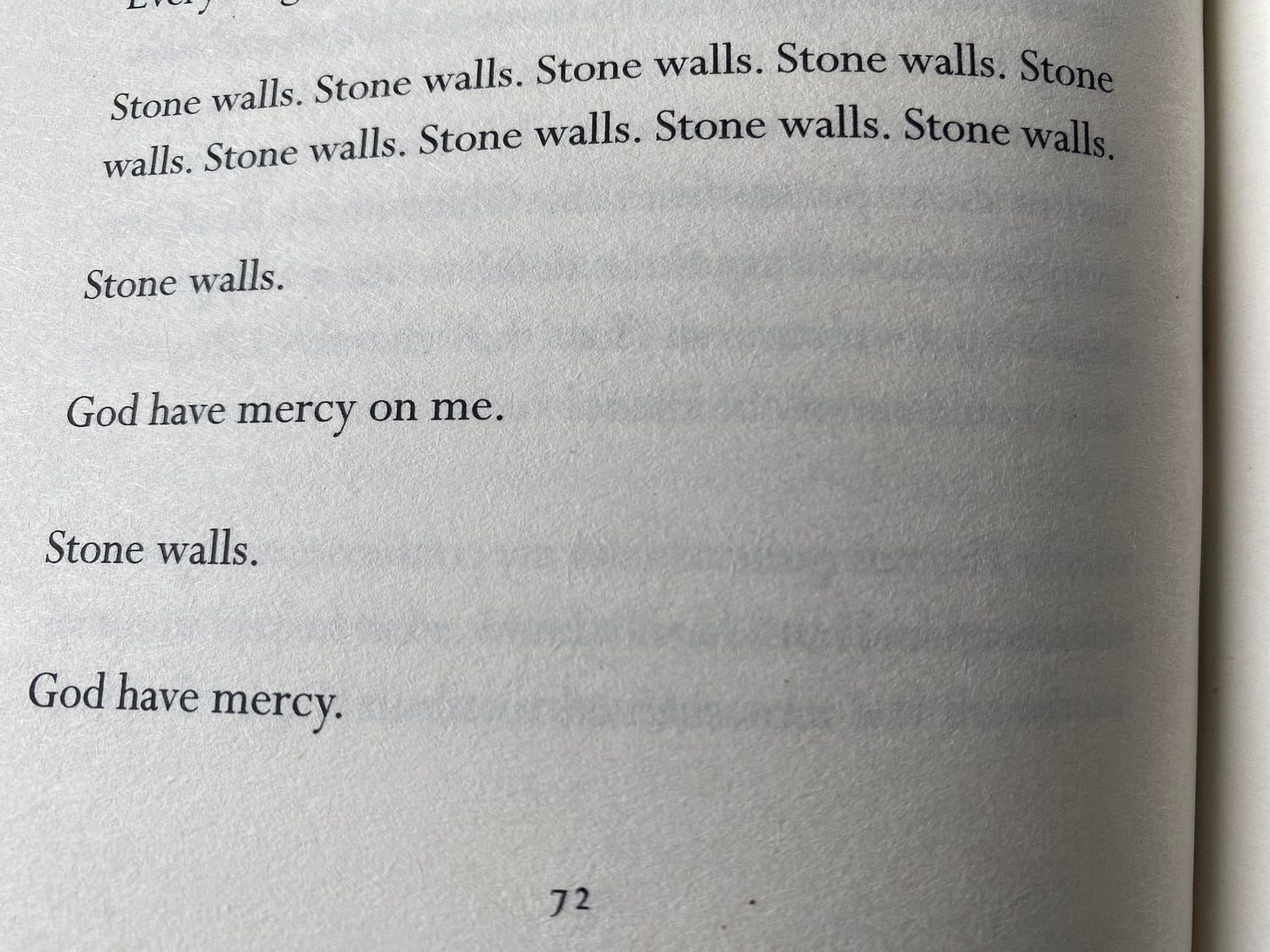

Poet turned novelist Victoria Mackenzie in her debut “for thy great pain have mercy on my little pain” used the layout of the words on the page to create a picture of Julian of Norwich’s incarceration as an anchoress in her cell.

The words are laid down like bricks on the page.

In “Several short sentences about writing” Klinkenborg has laid out his sentences as if they were poems, which forces me to slow down and look at each line,

to concentrate on each sentence.

To examine and question the punctuation and what it is doing.

I have been an avid reader all my life and yet here I am now needing reading glasses and still learning how to read.

Like Picasso says – it’s a life time’s work.

Try reading like a child, chanting your favourite lines out loud. Try reading as play rather than work.

One of your best Substacks ever. Now I must get the book!